Featured Report

US Economic Survey

SIFMA’s Economic Advisory Roundtable forecasts 1.8% GDP growth in 2025 and 2.2% in 2026, with upside risks from lower tariff impacts, productivity gains, and consumer spending. Inflation expectations remain anchored, though core PCE stays above 2%. “This is a notable improvement from the estimates made back in the 1H of 2025,” said Roundtable Co-Chair Scott Anderson, BMO.

Holiday Schedule

On behalf of financial markets participants, SIFMA recommends a holiday schedule for financial markets in the U.S., U.K. and Japan. Subscribe today to receive email alerts with the latest updates.

Latest Insights

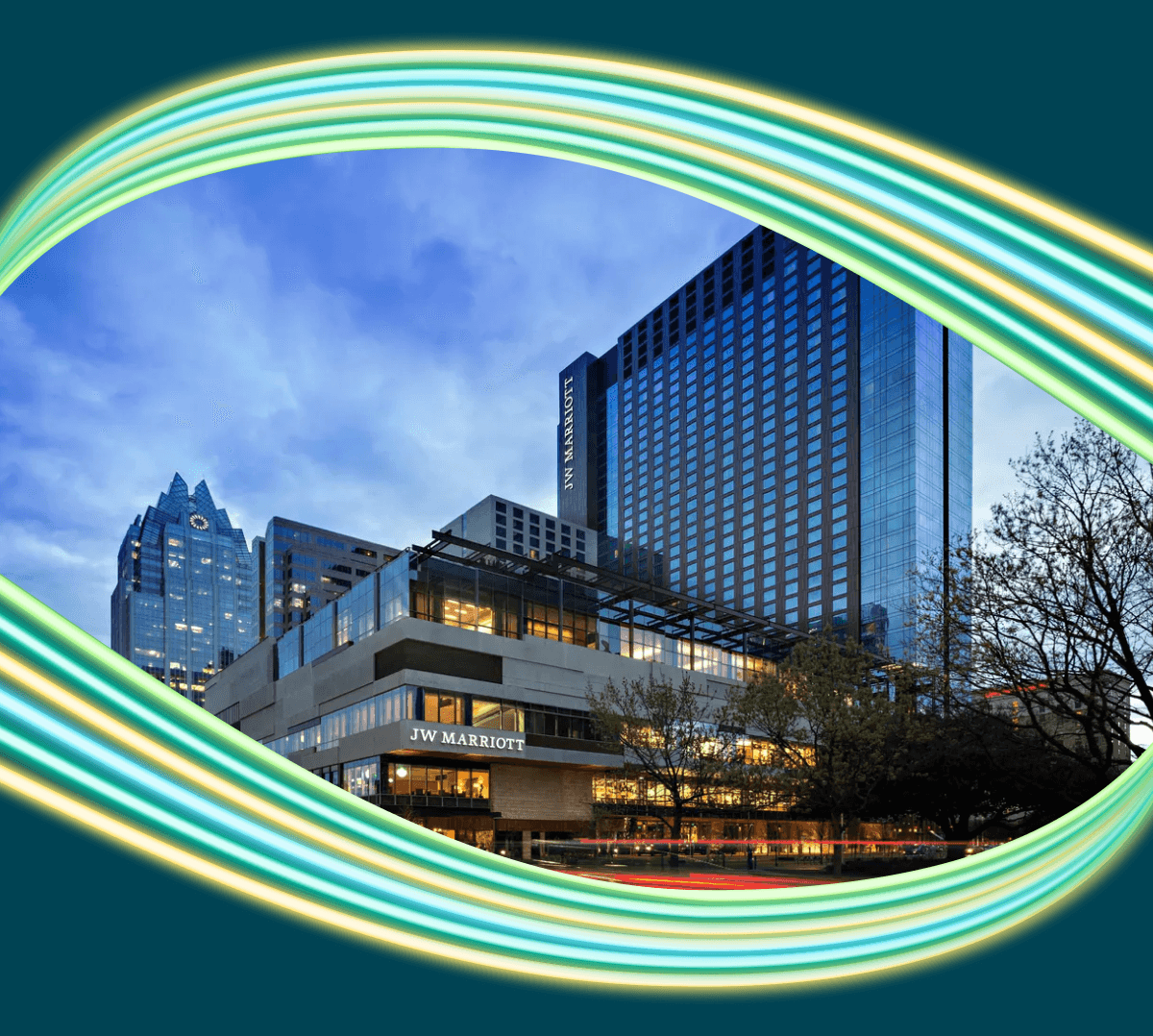

Upcoming Events

The foremost advocate for effective and resilient capital markets

- 500+Member Organizations

- 90%US Broker-Dealer Market Share

- $75T+Global Assets Under Management

- 100+Years of Industry Advocacy